From our limited anthropocentric (human-centered) perspective, we perceive only the

economic, political, and social manifestations associated with our “predicament”.

Since the mid/late 20th century, we in the industrialized West have resorted increasingly to

“pseudo purchasing power” in order to compensate for the increasing divergence between the

levels of real wealth created by our economies and our actual consumption levels.

Through pseudo purchasing power, we have been able to “augment” our consumption of natural

resources and derived goods and services during the past several decades—specifically by:

Liquidating our previously accumulated economic wealth reserves—e.g., depleting our

savings, “cashing out” our home equity, and selling our physical assets;

Exchanging ever-increasing quantities of fiat currency—“printed money” that has no intrinsic

value—for real wealth;

Incurring ever-increasing levels of unrepayable debt—at the personal, corporate, and

government levels; and

Underfunding investments critical to our future wellbeing—e.g., “social entitlements”,

pensions, retirement accounts, and infrastructure upgrades and maintenance.

While living beyond our means economically has enabled us to maintain (temporarily) the

industrialized lifestyles to which we in the West have become accustomed; our unsustainable

fiscal profligacy has also caused increasingly frequent and severe economic bubbles and

recessions, which in turn have caused intensifying political instability and social unrest.

But these are merely symptoms of our predicament.

Regrettably, due to our limited anthropocentric perspective, we cannot possibly

comprehend the ecological cause underlying our “predicament”.

Our industrialized existence is enabled almost exclusively by enormous and continuously

increasing supplies of the nonrenewable natural resources (NNRs)—fossil fuels, metals, and

nonmetallic minerals—that serve as the raw material inputs to our industrialized economies, as

the building blocks that comprise our industrialized infrastructure and support systems, and as the

primary energy sources that power our industrialized societies.

As an example, NNRs comprise approximately 95% of the raw material inputs to the US economy

each year. America currently (2008) uses nearly 6.5 billion tons of newly mined NNRs per

annum—an almost inconceivable 162,000% increase since the year 1800—which equates to

approximately 43,000 pounds yearly per US citizen.

Ironically, through our incessant pursuit of global industrialism, we have been eliminating—

persistently and systematically—the finite and non-replenishing NNRs upon which our

industrialized way of life and our very existence depend.

And because the natural resource utilization behavior that enables our current “success”—our

industrialized way of life—and that is essential to perpetuating our success, is simultaneously

undermining our very existence, neither our natural resource utilization behavior nor our industrial

lifestyle paradigm is sustainable.

This is our predicament.

More regrettably, the implicit assumption underlying our limited anthropocentric

perspective is that there will always be “enough” NNRs to perpetuate our industrial

lifestyle paradigm—and that humankind need only be concerned with using these NNRs to

provide ever-improving material living standards for ever-increasing numbers of our everexpanding

global population.

Unfortunately, the fundamental assumption underlying our anthropocentric perspective is wrong.

While there will always be plenty of NNRs in the ground, there are not enough economically

viable NNRs in the ground to perpetuate our industrial lifestyle paradigm.

Our ever-increasing global NNR requirements are manifesting themselves within the context of

increasingly-constrained—i.e., increasingly expensive, lower quality—NNR supplies.

NNR discoveries are fewer in number, smaller in size, less accessible, and of lower grade

and purity; and NNR exploration, extraction, production, and processing technologies are

experiencing diminishing marginal investment returns—i.e., each incremental unit of

technology investment yields smaller quantities of economically viable NNRs; while

Our global NNR requirements are increasing at historically unprecedented rates. Whereas

approximately 1.5 billion people occupied industrialized and industrializing nations in the late

20th century, that number currently exceeds 5 billion, most of whom have yet to even remotely

approach their full NNR utilization potential.

The unfortunate consequence associated with this “demand/supply imbalance” is that the earth

cannot physically support humanity’s current—much less continuously increasing—NNR

requirements going forward.

Global NNR scarcity was inevitable; the persistent utilization of finite and non-replenishing NNRs,

especially at levels required to perpetuate our industrial lifestyle paradigm, is unsustainable by

definition. Our quest for global industrialism during the past several decades merely expedited the

onset of epidemic global NNR scarcity.

In fact by 2008, immediately prior to the Great Recession, global NNR scarcity had become

epidemic. Sixty three (63) of the 89 NNRs that enable our modern industrial existence—including

aluminum, chromium, coal, copper, gypsum, iron/steel, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum,

natural gas, oil, phosphate rock, potash, rare earth minerals, titanium, tungsten, uranium,

vanadium, and zinc—were scarce globally in 2008.

At the time this essay is being written in February 2012, the vast majority of NNRs are:

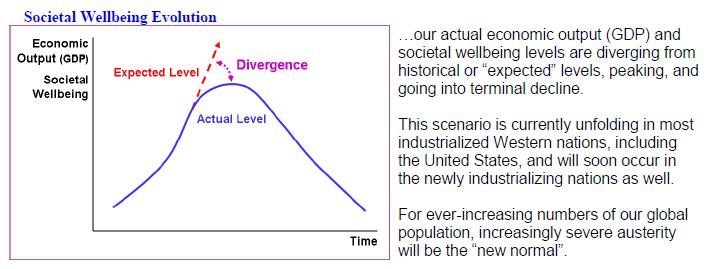

As an increasing number of NNRs become increasingly scarce …

Diminishing NNR Input → Diminishing Economic Output (GDP) →

Diminishing Societal Wellbeing (Population Level and Material Living Standards)

Most regrettably, given our limited anthropocentric perspective, we believe that the

underlying cause associated with our predicament is “systemic”; and that our

predicament can be remedied by improving or replacing our existing economic, political,

and social systems.

Wrong again. The fundamental cause underlying our predicament is ecological—ever-increasing

NNR scarcity—it is not systemic. Neither our incessant barrage of economic, political, and social

“fixes” nor the wholesale replacement of our allegedly “defective” economic, political, and social

systems will enable us to extract enough economically viable NNRs to perpetuate our industrial

lifestyle paradigm going forward.

Metaphorically, our well is running dry, yet we insist on tinkering with the pump.

Our historical reality of “continuously more and more”—which we in the industrialized West have

experienced since the inception of our industrial revolution and have come to take for granted—is

giving way to our new reality of “continuously less and less”, for geological reasons that are totally

beyond our control.

Our transition to a sustainable lifestyle paradigm, within which a drastically reduced subset of our

current global population will experience pre-industrial, subsistence level material living

standards, is therefore both inevitable and imminent.

And because we are culturally incapable of orchestrating a voluntary transition to sustainability,

our transition will occur catastrophically, through self-inflicted global societal collapse. All

industrialized and industrializing nations, irrespective of their economic and political orientations,

will collapse, taking the aid-dependent, non-industrialized world with them.

We are the pathetic victims of a tragic predicament of our own inadvertent creation, which is

beyond our collective capacity to “fix”; nor can we possibly prepare for its inevitably catastrophic

and chaotic consequences.

While a “solution” to our predicament—which would enable us to perpetuate our industrial

lifestyle paradigm for the indefinite future—does not exist; an “intelligent response” to our

predicament—which would enable us to avert global societal collapse—might exist.

However, for reasons ranging from ignorance to denial, we as a species have failed to seek,

much less to formulate, an intelligent response to our predicament.

Most people are completely unaware of the fact that our industrial lifestyle paradigm and our

industrialized economies are enabled almost exclusively by enormous and ever-increasing

quantities of finite, non-replenishing, and increasingly scarce NNRs. They cannot, therefore,

possibly understand that ever-increasing NNR scarcity is responsible for our current

economic deterioration, political instability, and social unrest; and, more importantly, for the

imminent demise of our industrialized way of life.

Too, most people have a strong vested interest, either as current participants or as aspirants,

in perpetuating our industrial lifestyle paradigm. Those who are aware of our predicament

and of its catastrophic consequences often choose to deny a reality that they consider too

unpleasant or too inconvenient to contemplate.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of our influential “thought leaders”—business executives,

politicians, academics, economic/political analysts, media commentators, social activists, and

other “concerned citizens”—remain ignorant or in denial; and thereby perpetuate ignorance on

the part of the general public, either unintentionally or intentionally.

Most unfortunately, while the probability that we can formulate and implement an intelligent

response to our predicament, thereby mitigating its catastrophic consequences, is certainly very

small; the probability that we will experience imminent global societal collapse in the event that

we remain ignorant or in denial and fail to respond intelligently is 100%.

Metaphorically, ever-increasing NNR scarcity is exerting a relentless, remorseless squeeze, like a

vise tightening around the collective skulls of humanity. And while the vise handle turns almost

imperceptibly at only 1/1000 of a revolution per day, the handle will make 3 complete revolutions

within the next 10 years, 6 complete revolutions within the next 20 years, 9 complete revolutions

within the next 30 years...

In the absence of an intelligent response to our predicament, humanity will crack somewhere

along the way.

We have backed ourselves into a corner from which an escape—should any of us manage

to escape—will be horrifically painful.

Our industrial lifestyle paradigm is not sustainable—it must and will end, soon;

Sustainability is not optional—we will be sustainable, either voluntarily or involuntarily;

A voluntary transition to sustainability would involve draconian reductions in our population

level and material living standards;

An involuntary transition could easily engender the extinction of our species.

NNR scarcity is the most daunting challenge ever to confront humanity.

If we Homo sapiens are truly an exceptional species, now is the time to prove it.

Note: for supporting evidence and references, please request a draft copy of my forthcoming

book “Scarcity—Humanity’s Final Chapter?” Contact: coclugston@gmail.com

Chris Clugston worked for thirty years in the high technology electronics industry, primarily with information technology sector companies. He held management level positions in marketing, sales, finance, and M&A, prior to becoming a corporate chief executive and later a management consultant. Since 2006, he has conducted extensive independent research into the area of “sustainability”, with a focus on nonrenewable natural resource (NNR) scarcity. He has sought to quantify, from a combined ecological and economic perspective, the extent to which America and humanity are living unsustainably beyond their means, and to articulate the causes, magnitude, implications, and consequences associated with this “predicament”. Mr. Clugston holds an AB/Political Science, Magna Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Penn State University, and an MBA/Finance with High Distinction from Temple University. He can be contacted at coclugston@gmail.com.