The idea that 2⁰C is a safe guardrail against global heating was a guesstimate by an economist almost fifty years ago, and it had a sketchy scientific basis even at that time. In November 2023, a consortium comprised of many of the top glaciologists and climate scientists in the world published a report entitled “The State of the Cryosphere 2023—Two Degrees is Too High.” (See also the review on Carbon Brief.) The only hope of preventing catastrophic sea-level rise, the authors say, is to cool the planet to a temperature anomaly of not much more than 1⁰C, as soon as possible. In a time of unrelenting bad news for the climate, no one wants to hear a prescription like this. But climate policy must be adjusted—quickly—to reflect this grim reality.

I am a philosopher of science, not a scientist, and certainly not a glaciologist. However, I have done what anyone can do, which is listen to and read what the glaciologists have to say. My aim here is simply to outline some very important things that glaciologists and other earth scientists have been trying for a long time to tell us about ice, and why it matters to anyone who cares whether our fractious species could have any sort of a sustainable future.

What Everyone Needs to Know

My focus is on ice melt and the resulting sea-level rise because policymakers and the public do not widely understand the immediacy of this problem. Here is the key finding of the study published by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI): “A compelling number of new studies . . . point to a [melt] threshold for both Greenland and parts of Antarctica well below 2°C, committing the planet to between 12–20 meters of sea-level rise if 2°C becomes the new constant Earth temperature.”

This implies that 2°C is not a guardrail beyond which the effects of carbonization would become unacceptable, but a point at which climate catastrophe is guaranteed. This report and other results imply that current climate agreements (based on staying within the 2°C limit and “aspirationally” holding to 1.5°C) are hopelessly inadequate.

This report came out just before COP28 in late 2023. It has received almost no notice or discussion in major media outlets. It was certainly not considered in any decision-making that occurred at COP28.

The result described in this report is not a new idea. In 2013, G. L. Foster and E. J. Rohling published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in which they stated, “[O]ur results imply that acceptance of a long-term 2°C warming [CO2 between 400 and 450 ppm] would mean acceptance of likely (68% confidence) long-term sea-level rise by more than 9 m above the present. Future studies may improve this estimate…”

Indeed, future studies have only made the estimate higher. Note that this paper appeared before the Paris Agreement of 2015, which set 2°C as the world’s climate policy goal.

Other scientists warned about catastrophic sea-level rise well before 2015. In 2007, James Hansen stated, “The nonlinearity of the ice sheet problem makes it impossible to accurately predict the sea-level rise change on a specific date. However, as a physicist, I find it almost inconceivable that BAU [business as usual] climate change would not yield a sea level rise change of the order of meters on the century timescale.”

And as far back as 1978, prescient glacier whisperer John H. Mercer made two key predictions:

“If the CO2 greenhouse effect is magnified in high latitudes, as now seems likely, deglaciation of West Antarctica would probably be the first disastrous result of continued fossil fuel consumption.”

“One of the warning signs that a dangerous warming trend is under way in Antarctica will be the breakup of the ice shelves on both coasts of the Antarctic Peninsula, starting with the northernmost and extending gradually southward.”

In 1995 the Larsen A ice shelf, at the tip of the Peninsula, blew apart overnight, and in 2002 Larsen B, a sheet of ice about 200 meters thick and having an area greater than the state of Rhode Island, crumbled in a few weeks. Mercer also correctly predicted that the center of WAIS (the West Antarctic Ice Sheet) would begin to thin.

Mercer’s predictions were not tied to any particular temperature increase. However, note his statement that deglaciation would likely be the first disastrous consequence of our fossil fuel addiction, not something that would conveniently occur long after the terms of office of our present political leadership.

António Guterres, Secretary General of the United Nations, deserves credit for recently warning that seas may rise to “unthinkable” levels and threaten “a mass exodus of entire populations on a biblical scale.” But policymakers have largely ignored the decades-long warnings of scientists about catastrophic sea-level rise.

How Much Could Sea Level Rise?—And How Fast?

There is nothing sacred about our present sea-level rise. Throughout geological history sea-level rises have see-sawed up and down, sensitive to small variations in climate. If all the present ice in the world were to melt, it would raise ocean levels between 65 and 70 meters. Seven would come from Greenland, roughly 58 from Antarctica, a few more from the various mountain glaciers and ice sheets around the world, and some from thermal expansion of sea water in a warming world.

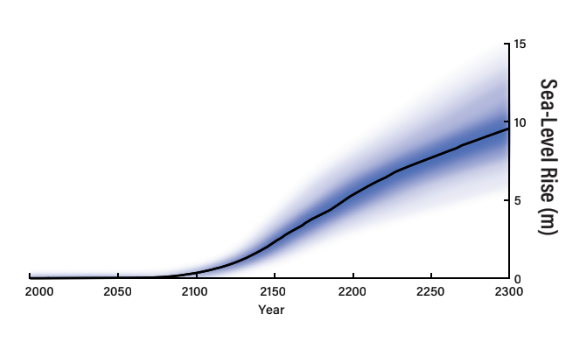

No one thinks that all 70 meters worth of ice could melt anytime soon. But numerous studies show that we are already at carbon dioxide and temperature levels consistent with seas 20 meters or more higher than we have now. As Hansen’s remark indicates, it is difficult to predict precisely how fast or exactly when this much sea-level rise could occur. However, policymakers should grasp that it likely would take the form of a steadily accelerating increase punctuated by abrupt, unpredictable, and irreversible pulses as ice sheets collapse, one by one.

Sea-level rise from Antarctica if current emissions continue. Source: ICCI.

Click the image to enlarge

|

To understand why this is the case, we have to know something about ice. For our purposes, there are three main kinds of ice in the world: ice on land (icefields, mountain glaciers, land-based ice caps); floating ice (sea ice and ice shelves); and marine ice sheets (also called marine terminating glaciers). The latter kind of ice is the wild card, for reasons everyone needs to understand.

If land-based ice melts, it is simple—sooner or later the water ends up in the sea. Melting is a major mechanism of ice loss in Greenland.

The melting of the second type of ice, sea ice and ice shelves, has at least three major effects on the earth system: Darker open water absorbs much more solar radiation than ice, so that the melting of sea ice, which replaces reflective ice cover with absorptive dark water, is one way in which warming causes more warming. Also, ice shelves buttress the land-based and marine-terminating glaciers behind them, and when the shelves disappear, the glaciers can flow into the sea much faster, which of course does raise sea-level rise. Furthermore, the loss of sea ice and ice shelves will have disastrous effects on marine biota.

Ice Over Flotation, and Why it Matters

To understand the risk posed by grounded marine ice sheets—the third, critical group—we need to understand the important concept of “ice over flotation.”

Imagine a stack of old-fashioned ice blocks in a bathtub containing about a foot of water. The ice sits on the bottom of the tub because it is too heavy to float. This is ice over flotation—more ice than can float in a given footprint and depth of water. The more blocks of ice you add to the stack, the higher the water level will go when it ultimately melts.

Marine ice sheets are like our bathtub in that they contain huge amounts of ice over flotation. Over millennia, snow builds up within a geographical basin and compresses into blue ice, which accumulates faster than it can flow out of the basin. The vast weight of the ice compresses the earth’s crust, making the basin deeper and allowing for even more ice buildup.

Grounded marine ice sheets can remain stable for thousands of years so long as the climate remains cold enough and they are protected from the open sea by ice shelves. But if relatively warm sea water gets access to the base of the ice domes, they can collapse catastrophically, possibly even within a few years (though how fast remains a matter of investigation).

If the calving face (the often-turbulent ice cliff where icebergs break off into the sea) eats into the heart of the ice sheet, there are several feedbacks that can cause the collapse to accelerate. (For more detail, see my CACOR talk.) Glaciologists speak of Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI)—the deeper into the interior basin the calving front goes, the faster the ice crumbles. Studies of paleoclimate show that on rare occasions the collapse of ice masses can lead to several meters of sea-level rise per century.

Here’s the catch: The chain of events that would trigger such a catastrophe could be set in motion many years before the event itself. And like a slow-motion avalanche, it might be unstoppable beyond a certain point no matter how much we reduce emissions or recycle our beer cans. In an important sense the question, “How long would it take for the predicted 12–20 meters to cash out?” is not relevant. There is absolutely no scope for delay.

Hence, our climate policy should be guided not by the principle of brinkmanship (“how close to the edge can we skate?”), but by the precautionary principle (“we don’t want to go there”). Climate brinkmanship is very similar to nuclear brinkmanship except that we play chicken not with other nations, but with the entire planetary ecosystem. Although current climate policy affects the pretense of sober cost-benefit analysis, it is in fact a form of high-stakes gambling.

What Worries Me

A cynical old saw is, “We have the morals we can afford.” Writers like Naomi Klein believe that solving the climate problem will force us to solve the larger problem of the predatory nature of most human interactions and move humanity to a new level of equity and cooperation.

I would like to think that this is the way it will go. The problem is that as we get closer to stark emergency, it will be harder to respond in ways that are measured and equitable. If there is any hope of saving West Antarctica, it will involve some combination of emissions reduction, fossil fuel replacement, improved land management, direct air capture of carbon, and possibly solar radiation management, applied on an emergency basis and not merely when it is politically and economically convenient.

As the situation becomes more dire, our increasingly desperate responses are likely to become more technocratic, risky, and unilateral. Humanity might squeak through the climate bottleneck, only to be left with a world that is even more inhumane and unjust than the one we have now. We really should listen to what those glaciologists are saying.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kent Peacock is a professor of philosophy at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada. He is mostly a philosopher of science who works on the philosophies of physics and ecology, with occasional excursions into logic. He also has strong interests in the metaphysics of time, environmental ethics, professional ethics, ancient philosophy, the nature of ingenuity and creativity, and the complex of challenges flowing out of humanity's current ecological crisis. He believes passionately that philosophy is not merely an exercise in idle curiosity, but (if done well) a vitally important tool for human survival.

|